Software estimates suck

TL:DR: Estimations waste time. Design well, derisk early, ship small, and invest in quality.

I rarely have definite opinions about anything, but, if a genie granted me three wishes, my first would be to make everyone on Earth forget about software estimates. My second and third wishes would be the same!

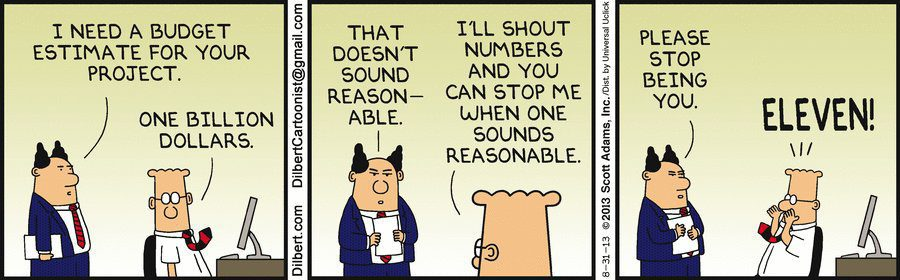

Software estimates suck, here are a few symptoms why:

- Estimates are hard to do and rarely accurate.

- Estimates create debates on “how long it is going to take ?” instead of “how are we going to make it ?”

- Estimates rituals are often tedious and full of friction. They’re poorly perceived by team members, tend to drag on longer than needed, and drain everyone’s energy.

- Teams spend a lot of energy on improving their estimation process (story point vs man days, poker planning, three-point estimation, bottom-up estimation, t-shirt sizes, Fibonacci sequence, …).

- Estimates can lead to two extremes: “always late” feeling, or being superconservative.

- Experienced Product Managers use random factors on original estimates when communicating timelines (up to x3 🤯)

- Lots of cognitive bias happen when estimating (anchoring bias, planning fallacy, confirmation bias, …)

- We do estimates when we have the least information about a project (i.e. before starting it).

- Worst case scenario, developers discover a project when they start estimating it

- We mix estimates with software design discussions.

I haven’t been in an estimation meeting for years. It’s because I choose to join teams that are already not doing them, or I deliberately evangelise against it and help teams to transition away from estimates.

Based on experience, this post lists some topics I believe are more important to focus on, instead of doing estimates.

Do explicit software design sessions instead of software estimates

The biggest value in estimating isn’t the estimate but checking if there is a common understanding.

Instead of doing a long and tedious estimation meetings with a large audience, I’d rather split it down into several dedicated software design sessions (one per topic), inviting only team members who have “skin in the game”.

In a software design session, we focus on “How are we going to build it ?” Instead of asking “How long will it take?”. It means jotting down architecture ideas on a white board, exploring existing code bases, deciding to invest on a Proof Of Concept (POC) or a spike, defining an incremental release strategy, …

Those sessions are fun (and sometimes heated), and team members usually leave energised and eager to start.

Invest into derisking

Does the following situation sound familiar?

A big project is broken down into a bunch of epic/stories, everything looks good on paper, everybody is happy and confident. Implementation begins, and we soon start discovering technical difficulties one after another, increasing delivery time and challenging the original implementation strategy of the project. The actual implementation is harder or way different to what was originally imagined. Pressure builds up, stakeholder get impatient, developers lose motivation. That’s usually when we start compromising on quality, implement hacks, and take unintentional technical debt.

Most of the time, these situations could be avoided by proactively investing in Proofs of Concept (POCs) or Spikes.

A POC or Spike allows a team to explore unknowns before making commitments. It’s a focused, timeboxed effort meant to answer a specific question: Can we actually build this the way we think we can? It helps identify hidden complexity, technical limitations, or missing domain knowledge—long before those risks show up during implementation.

This investment up front drastically reduces downstream surprises. It’s not wasted time; it’s buying clarity. It’s the difference between confidently walking a clear path versus discovering the ground is shaky while you’re already halfway across.

Deadlines and Timeboxes over Estimates

Parkinson’s law tells us that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion”, which, to my ears, sound like another way of saying estimates do not make sense.

Changing the question from “How long is it going to take ?”, to “How much time do we want to invest in this topic ?” is very powerful.

Deadlines and explicit timeboxing, when realistically chosen and set by the team doing the work, are very powerful tools. It usually fosters a “let’s make it happen” mindset and triggers prioritisation topics.

Start with the hardest part first

A smart prioritisation is key to a successful project delivery. Once a project is broken down, some engineering teams naturally tend to start with the easiest parts first. The ones where there is little uncertainty, where the implementation path is crystal clear, where similar tasks were already done. It’s also usually the ones bringing low value to the end user.

While this is comforting and generates dopamine (nothing better than quickly closing a bunch of small tickets), this might not be the best strategy.

Similarly to derisking, I would generally nudge a team to start a project with the hardest topic first. The one people shy away from, the one “we’ll figure later”, the one with many different implementation strategies, the one with the most uncertainty. That’s the topic that has the highest probability to make us miss a deadline or derail a project. We want to discover those issues as early as possible.

Adopt a Pull-Based Mindset Instead of Pushing Work into Timeframes

Traditional sprint-based planning often relies on pushing a fixed amount of estimated work into a set timeframe—usually two weeks. Teams fill up the sprint with story points or tickets, commit to a scope, and then race against the clock to complete everything. This creates artificial pressure and often turns into a game of estimation, velocity tracking, and rollover excuses.

Lean thinking flips this on its head.

Rather than pushing work in, we pull work through the system when there’s capacity. The focus shifts from “Did we deliver everything we planned for this sprint?” to “How quickly can we get value to customers?”

This mindset encourages:

- Flow efficiency over resource efficiency: Keep work moving, not people busy.

- Shorter lead time: Measure how long it takes from idea to value delivery, not how well you predicted the work.

- Continuous deployment: Ship code when it’s ready, not when a calendar says it’s sprint demo day. The sooner it hits production, the sooner it starts generating feedback or value.

- Outcome-focused metrics: Track time to first customer feedback instead of story points burned. It’s a much better proxy for how aligned you are with user needs and how quickly you’re learning.

This approach is liberating. It puts the spotlight on delivering real value, not on guessing how long something will take—and then pretending it means anything when reality hits.

Small, iterative, and frequent releases

Iterative releases, continuous integration/deployment (CI/CD), and early testing/security integration (“shift left”) are your allies here.

Instead of waiting until everything is “done” to ship, embrace a mindset of continuous delivery. Break work down into the smallest possible valuable units and release them early and often. Each release is an opportunity to validate assumptions, detect integration issues, gather feedback, and maintain momentum.

By integrating testing and security checks early in the development process (“shift left”), teams can catch issues where they’re cheapest to fix—before they become deeply embedded problems. Combined with a CI/CD pipeline, this means your code is always in a deployable state, and any new changes go live with confidence and minimal overhead.

Shipping small and often also makes estimations largely irrelevant—you focus instead on flow, feedback loops, and steady value delivery.

Focus on improving quality, not estimates

“When you suck at building software, your estimates will suck. When you’re great at building software, your estimates will be mediocre.”

Spending excessive energy on refining estimation techniques instead of addressing fundamental engineering problems is a classic case of treating the symptom, not the disease.

Teams often obsess over getting better at estimating—debating whether to use Fibonacci points, man-days, or story sizes—while ignoring the root causes of delays: poor code quality, unclear requirements, weak collaboration, lack of automated testing, or brittle infrastructure.

Improving engineering practices—through pair programming, robust automated tests, meaningful code reviews, strong documentation, and a culture of continuous improvement—creates more predictable and maintainable software. With higher quality, surprises decrease, and delivery becomes more stable.

Estimates improve as a side effect of better engineering. But chasing better estimates without investing in better delivery? That’s just painting over a crumbling wall.

Common Pushbacks Against Ditching Estimates (And How I Usually Respond)

Not everyone is ready to let go of software estimation. That’s fair. But over time, I’ve encountered a few recurring objections—and here’s how I typically address them:

→ “We need to know in advance how much it’s going to cost.”

Yes, of course—we live in the real world, and budgets are a thing. But here’s the catch: what most stakeholders really need is a sense of scale, not a precise estimate. They want to know: Is this a week-long task, a month-long initiative, or a multi-quarter investment?

The reality is, in early-stage planning, any number you give is going to be wrong—wildly so. So instead of pretending precision exists where it doesn’t, I recommend setting internal deadlines or timeboxes based on how much time or budget we’re willing to invest to explore or deliver something.

Ask instead: What value do we expect in return if we spend X amount of time/money? That’s a healthier conversation than trying to forecast cost through unreliable estimates.

Also, when needed, rough cost brackets or phased budget approvals tied to clearly defined delivery checkpoints (instead of story points) often do the job better.

→ “Without estimates, we can’t track progress.”

This one’s common, but also quite revealing: it assumes progress is measured by how much work has been completed. But in modern product development, burning through tasks is not the same as making progress.

The real question should be: Are we moving closer to delivering value?

If progress tracking is needed, shift the conversation toward outcomes and impact:

- Are we reducing user pain points?

- Are we increasing conversion or retention?

- Are we getting faster feedback from real users?

- Are we validating assumptions?

You can also track delivery flow using cycle time, lead time, or deployment frequency—all of which are far more actionable indicators of a healthy development process than percent-complete bars or story point burndowns.

If stakeholders still want visibility, short written check-ins, demos, or Kanban-style dashboards showing what’s in progress, blocked, or done provide far richer and more honest information than estimated velocity charts.

→ Sometimes, we have to use estimates

Yes, there are exceptions—like fixed-budget work or compliance-heavy environments—but those are the edge cases, not the norm.

Let’s talk: how does your team work without estimates?