A guide to the timeless laws of engineering excellence

While software engineering is one of the youngest branch of engineering (~60 years), it comes with its set of laws coined by engineers, scientists, economists, or psychologists, and based on facts gathered over time.

In this blog post, I am listing some software engineering laws I got exposed to over the years. I chose the ones I keep referencing regularly in software engineering discussions. I’m also giving pointers on how one can take them into account on a daily basis.

-

Conway’s law: Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

-

Metcalfe’s law: Every time you add a new user to a network, the number of connections increases proportionally to the square of the number of users

-

Galls’s law: A complex system that works has evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system built from scratch won’t work.

-

Parkison’s law: Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.

-

Hofstadter’s law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

-

Brook’s law: Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.

-

Goodhart’s law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure

1. Conway’s law

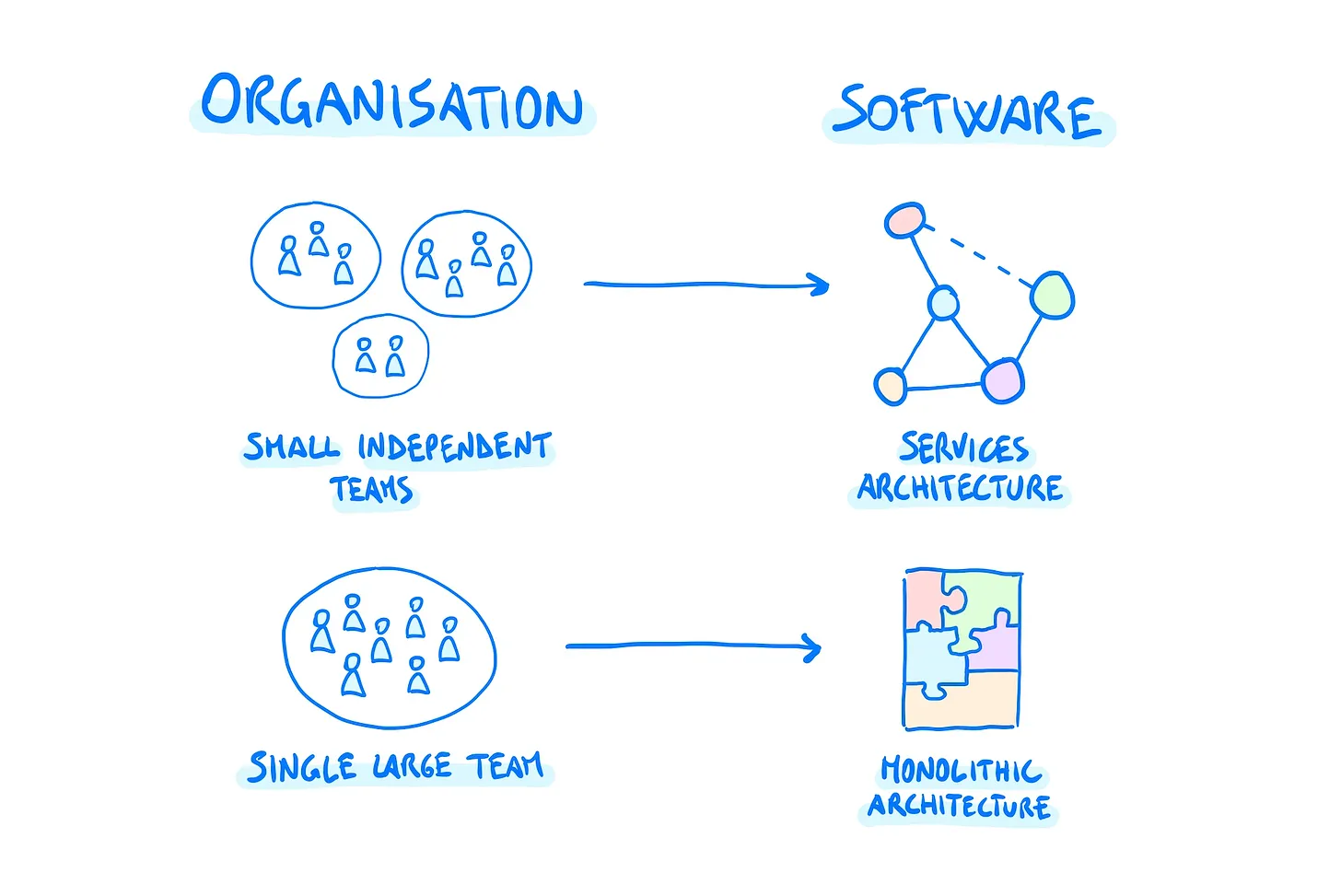

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

Why is it significant ?

Communication cost increases exponentially with the number of people in an organization.

Communication issues and System design limitations are tightly coupled.

How to use it ?

→ Recognize the impact of Conway’s Law as first step.

It helps to ensure that architectural choices or evolutions won’t conflict with current communication patterns in the organization. Or, if it does, this is signalling that current communication patterns will most likely have to evolve for the architecture changes to be efficient.

On typical example for Conway’s law is:

If you have four groups working on a compiler, you’ll get a 4-pass compiler.

Now, for instance, if we wanted to migrate to a 2-pass compiler, recognizing Conway’s law, it is a good idea to reorganize the four groups into two.

→ Alter the development team’s organization structure to encourage the desired software architecture.

It is called an “Inverse Conway Maneuver”.

Domain Driven Design, identifying Bounded Contexts, can also be a useful tool to take Conway’s law into consideration when architecting a software.

2. Metcalfe’s law

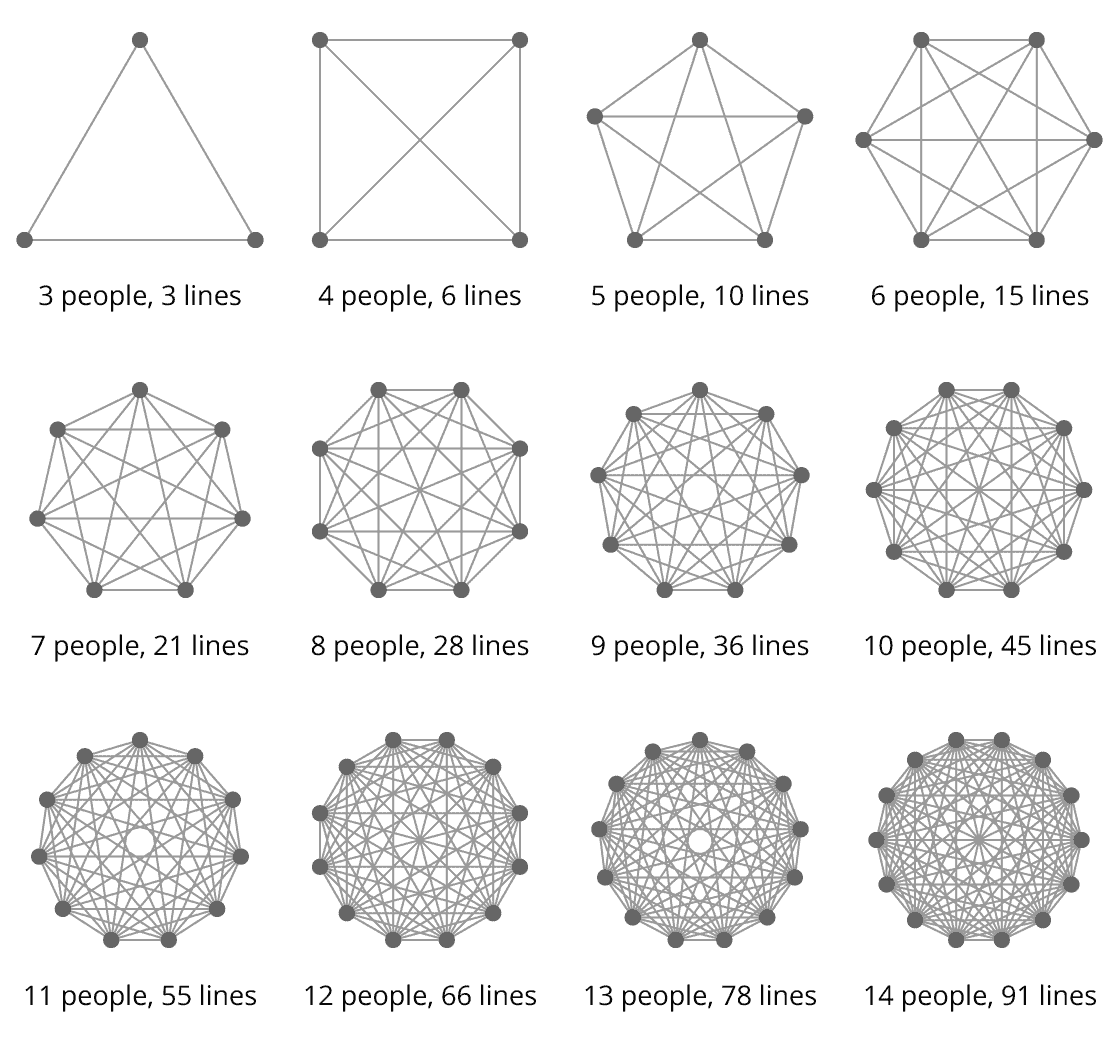

Every time you add a new user to a network, the number of connections increases proportionally to the square of the number of users

Coming from the telecommunication industry, Metcalfe’s law characterizes network communication effect in teams, groups, or communities.

As an image is wort a thousand words, below is a visualization of the number of individual communications possibles (”lines”) by group size.

Why is it significant ?

Communication cost increases exponentially with the number of people in an organization.

How to use it ?

→ Aim to organize teams or departments with the smallest group possible.

→ Before sending an invitation to a new meeting, ask yourself the following question:

What is the minimal group of people needed to achieve the goal of the meeting ?

3. Gall’s law

A complex system that works has evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system built from scratch won’t work.

Why is it significant ?

Designing a complex software from scratch is hard and has high probabilities of going wrong.

How to use it ?

→ Adopt a continuous improvement mindset and use iterative processes.

→ Start with basic solutions, reuse known to be working modules, and then release early and often.

4. Parkison’s law

Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.

Why is it significant ?

Software engineer time is expensive, the name of the game is to work on the right topic without wasting (too much) time.

How to use it ?

→ Set realistic and specific deadlines to avoid work expanding unnecessarily.

→ Use time-boxing techniques, where tasks are given a fixed time period to be completed, to encourage focus and efficiency.

→ Regularly review and adjust timelines to ensure they are appropriate and not overly padded.

5. Hofstadter’s law

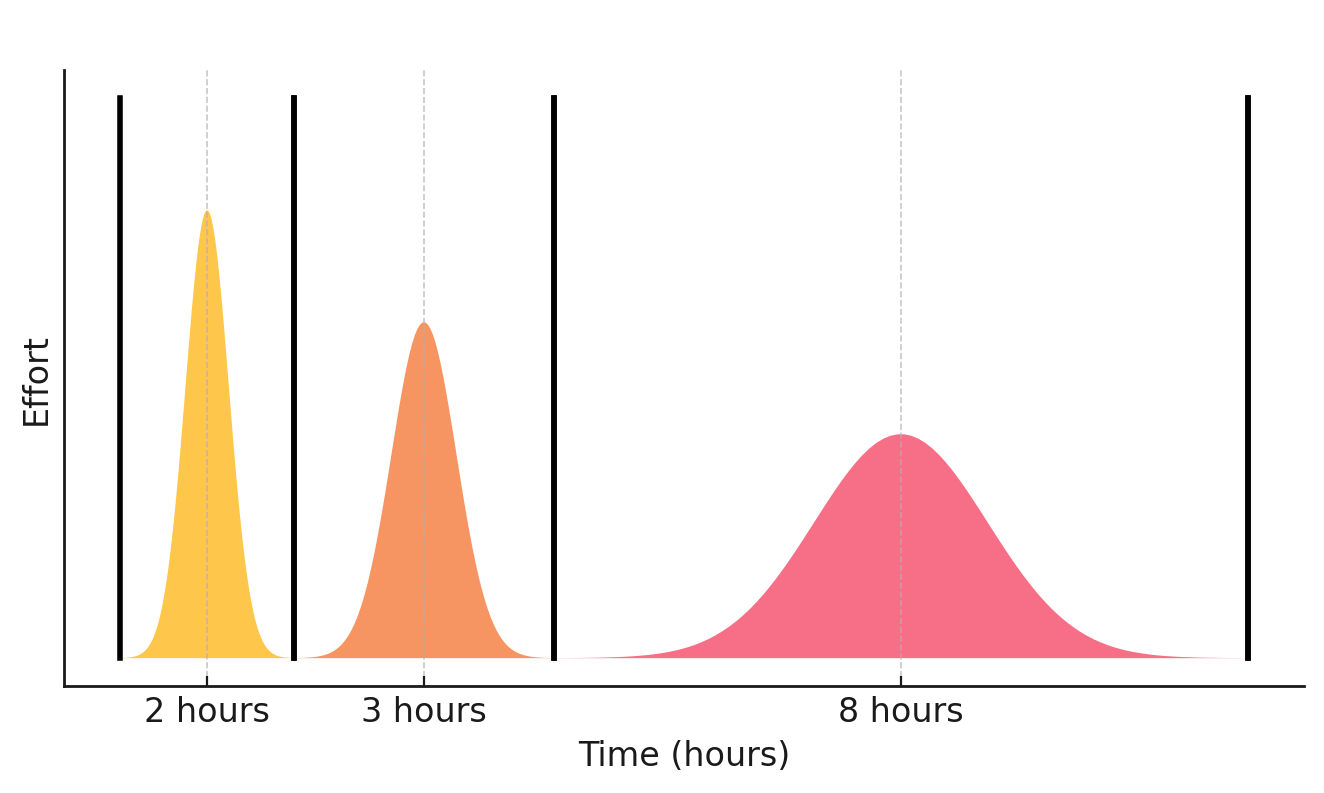

It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

Why is it significant ?

Overpromising on deadlines generates stress in software engineering teams and degrades relationship with stakeholders.

How to use it ?

→ Incorporate buffers into project timelines to account for the inherent unpredictability of software development.

→ Encourage regular status reviews and adjustments to timelines as the project progresses to accommodate unforeseen challenges.

6. Brook’s law

Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.

Why is it significant ?

As a tech leader, we are regularly exposed to late software projects and external pressure to deliver quicker. In such cases, it is easy to be tempted to add more resources to a project (i.e. trying to do a baby in one month with 9 women).

How to use it ?

→ Avoid adding more developers to a project close to deadlines.

Instead, remove non-key engineers from a project to allow the remaining core team to complete the project more quickly. Which is sometimes referred as “The Bermuda Plan” (send them to vacation in Bermuda)

7. Goodhart’s law

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure

Why is it significant ?

When a specific metric is used as a primary target or goal, the utility of that metric as an indicator of broader success diminishes. This happens because people may start optimizing solely for that metric, sometimes in ways that undermine the actual objective the metric was supposed to represent.

For instance, Code Coverage or Bug Counts are metrics that are subject to suffer from Goodhart’s law

How to use it ?

→ Be Cautious with Metrics

It is a good habit to mix quantitative and qualitative feedback.

→ Focus on Outcomes, rather than Outputs

Align metrics with business goals.

→ Use Metrics as Tools, Not Targets

They should provide insights that guide actions and improvements, rather than serve as rigid goals.

→ Avoid Metric Manipulation

Ensure that the metrics you use do not incentivize undesirable behavior, such as cutting corners or gaming the system.

Resources

https://blogs.oracle.com/javamagazine/post/curly-braces-java-brooks-law